Ladies and Gentlemen: Good morning!

First of all, let me thank the organizers for inviting me to participate in this conference. It is a pleasure to speak on today’s panel.

Before I begin, I would like to take a moment to recognize the achievements of the National Bank of Ukraine in enhancing its transparency. As I am sure you all aware, at the beginning of this year the Bank was awarded the prestigious international Transparency Award for making impressive efforts to increase its openness, including clear communication about the banking system and communicating monetary policy. I wish to express my congratulations on this accomplishment and for being on the right track.

As the Governor of the Bank of Lithuania and a member of the ECB Governing Council, today I will talk about communicating monetary policy – and not only about the ECB experience, but central bank communication in general – as part of the larger policy toolkit.

We’ve just heard stimulating presentations regarding the effects of forward guidance. The latter has become an essential tool to preserve an accommodative stance in the low interest rate environment that we have been witnessing in many advanced economies.

Forward guidance – in any form it comes – is used to influence market expectations by clearly communicating about possible future policy moves. This helps markets, businesses and consumers to better formulate expectations about future movements and adjust their actions accordingly.

We have to admit that, in times when the standard monetary policy instruments have been bounded, there is a need for a supplementary tool to help preserve market expectations, primarily about continuous accommodation in the economy. As such, communication about the possible trajectory of monetary policy tools (first, interest rates; later – also asset purchases) has become a distinct monetary policy tool unto itself.

To grasp the significance of this operational shift, we can recall that communication has not always been an item on the central banks’ agenda. Until not so long ago, central banks were rather secretive institutions: policy decisions were communicated in a very reserved way, to say the least. For example, the US Federal Reserve used to be silent even about interest rate decisions, leaving the outside world to use market reactions to discern those decisions.

This approach – that is looking from the so-called “high priests'” perspective – started changing back in the 90s. Since then, central banks have been gradually opening up: for instance, in the mid-90s – I would like to emphasize – only since the mid-90s – the US Federal Reserve started to publicly announce its interest rate decisions in real time – something that policymakers had previously deemed unnecessary. The ECB, for its part, has not always been as transparent about monetary policy as it is now. For instance, the accounts of monetary policy meetings of the Governing Council began to be published publicly just a few years ago.

So, what has changed? I suppose that there are two main factors to consider.

First, while being independent institutions, central banks have become increasingly accountable to the general public. This accountability leads to building public confidence through more intensive communication about monetary policy: explaining decisions based on the economic situation as well as on policymakers’ goals. In essence, this helps strengthen the perception that a central bank is able to fulfil its mandate of ensuring price stability. In other words, the purpose of more in-depth central bank communication is not only to reduce uncertainty, but also to bolster central bank credibility.

Second, the post-crisis low interest rate environment laid the ground for central bank communication to play a key role, and also for it to become much more forward-looking. Economic agents act in a forward-looking way, but they must manage a vast amount of information surrounded by a lot of uncertainty. As such, it is important to guide them to formulate appropriate expectations. Ultimately, a better understanding of policy makers’ actions enhances the transmission of central bank policies.

Hence, we started to use forward guidance as a monetary policy tool in and of itself. And, as you can see from the survey results in the graph, many central bank governors and academics claim that central bank communication has been intensifying. The use of this tool, moreover, is widespread: for example, all major central banks globally used it in order to achieve adequate accommodation in the past decade.

Having discussed the aims of forward guidance, I would now like to touch upon two related issues, namely, its effectiveness and its future.

In the previous session, we heard discussions on the effectiveness of forward guidance. I can affirm that, among policymakers, there is no doubt that forward guidance helps to steer expectations. Yet, the effects of forward guidance are not as straightforward as we might like them to be. Unsurprisingly, the results depend on a few things: first, on the particular form of forward guidance chosen; second, on the central bank’s credibility; and, finally, on agents’ private information and the general level of informational noise.

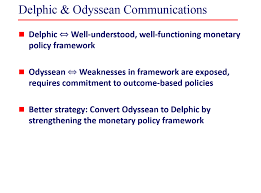

Although in practice forward guidance is rarely perceived in such pure terms, here I would like to distinguish between the so-called Delphic and Odyssean types. Delphic guidance is a statement of how policymakers see interest likely to evolve, but it makes no promises about future policy actions. In Odyssean guidance, by contrast, policymakers commit to some (contingent) actions in the future.

The horizon of Odyssean guidance can be state-contingent, have an end date, or even be left open-ended. For example, currently, the ECB’s forward guidance is that interest rates are expected to remain unchanged at least through the end of this year. Research indicates that different types of forward guidance differ systematically in how they impact on expectations and reduce disagreements in the markets about the future path of interest rates. More detailed, specific forward guidance – such as time- and state-contingent Odyssean guidance – seems to be more effective in guiding expectations.

Intuitively, this effect makes sense: such central bank communication tones down some of the informational noise and diminishes uncertainty. Nonetheless, this statement should not be interpreted as advocating any particular type of guidance, as the effects should depend on the interest-rate environment in which we are living.

Thus, in times of low interest rates, we strengthen forward guidance and make it more explicit. When interest rates are not bounded (and are, therefore, at higher levels), we can rely on a ‘lighter’ form of guidance.

Going further, any discussion on forward guidance would be incomplete without touching upon the controversy regarding “who is leading who” in this “game” of exchanging information. Is the central bank leading the financial markets, or have central banks become overly dependent on the market reaction function? In other words, are we “catering” to the markets? Meaning, are we putting the needs of financial markets – that is, mainly private investors – before the needs of the real economy as a whole (price stability target)?

There are no simple answers to these questions. On the one hand, central banks have to take into account every nuance in the economy, including how financial markets might process implicit and explicit signals from the central bank. On the other hand, central banks should not solely rely on how the markets may or may not react.

We are all sailing in unchartered waters: the current high level of accommodation is unconventional, and we see that financial markets may have a heightened sensitivity to changes in monetary policy. Therefore, now that the major central banks are starting monetary policy normalization, we – policymakers – are extra careful, as we want to avoid destabilizing expectations that could prompt a negative market reaction. By a negative reaction, I mean that we could observe more rapid interest-rate increases in the markets than we consider necessary to reach our policy target.

This is why, with respect to forward guidance, balancing the pace and rhetoric of policy normalization with potential market reactions is crucial, even though such caution could be interpreted by some as “catering” to financial markets.

Finally, we arrive at the issue of the future use of forward guidance. As you can see from the graph, most scholars and central bank governors believe that forward guidance, in one form or another, will remain in the monetary policy toolkit. The survey is from 2016, and I believe this convention is even stronger today.

Is forward guidance here to stay, then? I believe it is. In what form? The answer to that question will depend, to a large extent, on the interest-rate environment. Moreover, the form itself is not so essential. The critical point is to remain open to the public; in this case, to hold steady central banks’ communication about the future trajectory of policy decisions.

In my view, there is no reason to remove a policy tool that has proven useful, even if the environment in which it was introduced evolves. The key role of forward guidance might lessen if standard tools are in play again. However, removing forward guidance from the toolkit – even in times when the effective lower bound is not binding – might be perceived as unwelcome closing-off in attitude.

Markets are now used to a certain amount of communication. Reducing this communication could run counter to the goal of transparency and, as a result, diminish the credibility required for effective monetary policy.

Moreover, less communication could be perceived as a negative signal, and thus cause unwanted market reactions. The current monetary policy normalization is unprecedented, and well-structured communication (providing guidance on how the central bank will proceed) is needed to smooth the process.

I believe that forward guidance has become an effective supplement to conventional tools; should we need another monetary easing cycle soon, conventional instruments would arguably play a less prominent role than in previous downturns.

To wrap up, I think it is safe to say that central bank communication has become a proper monetary policy tool. The statements following monetary policy meetings in every major central bank gather a substantial attention, and watchers analyse every sentence – down to the last word.

Consequently, any change in communication – either what is said or what is left unsaid – is immediately noticed and widely interpreted. To water down the statements into less detailed, more “reserved” language would be, in my opinion, going backwards in terms of the pursuit of greater transparency and credibility. It is worth bearing in mind that the latter is directly linked to achieving the core price stability target.

Thank you.